A negatively charged strangelet would have no coulomb barrier against absorption of normal matter, and would in fact attract it. The resulting exothermic reaction would simply produce a larger strangelet. Since the energy per baryon always decreases with A, a negatively charged strangelet on earth would continue to digest all of the matter it came into contact with until the earth itself was entirely strange.

Joshua Holden, The Story of Strangelets

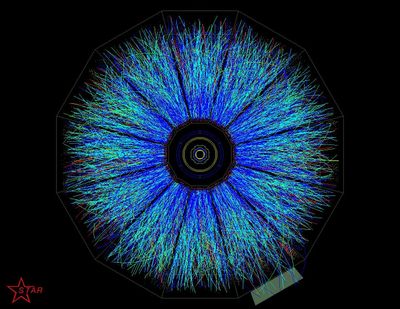

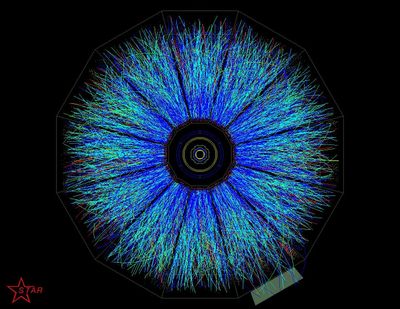

What is the scenario in which strangelet production at RHIC leads to catastrophe? The culprit would be a stable (or long-lived metastable) negatively charged strangelet produced at RHIC. Here we require a lifetime at least greater than 10-8 seconds--the time necessary to traverse the apparatus and reach the shielding. [I]t would react with [a] nucleus, and absorb several nucleons forming a larger strangelet. This process would continue until all available material had been converted to strange matter. We know of no barrier to the rapid growth of a dangerous strangelet.

Bob Jaffe, Frank Wilczek, Jack Sandweiss, and Wit Busza, "Review of Speculative 'Disaster Scenarios' at RHIC"

Strange matter was probably also created along with normal matter at the time of the expansion of the initial singularity, but because small strangelets (the kind that would have been created then, and now here at the RHIC) are unstable, they would have rapidly decayed (radioactively) into hadrons (normal matter), so that's why they are not normally found in nature. Hadron nuclei have a narrow regime of stability, with iron nuclei being the most stable. Energy can be obtained by fusing smaller nuclei (nuclear fusion) or by splitting heavier nuclei (nuclear fission). Strange matter, however, becomes more stable the bigger it gets, with small strangelets (the kind that would be produced in the RHIC) having a short half-life on the order of microseconds to milliseconds. Because it gets more stable as it grows (becoming fully stable at a mass of about 1000 protons), it will generate more energy as it fuses with normal matter. The normal matter will be absorbed by the strangelet and become part of the strange mass.

This possible disaster scenario was actually described in the BNL Review: a negatively charged strangelet condenses out of the quark-gluon plasma with a half-life more than a nano-second (10-9 second). That's enough time for the strangelet to traverse the vacuum in the RHIC, penetrate the iron wall (being slowed to thermal velocity in the process) and mingle with the helium atoms in the super-conducting magnet cooling jacket. Spontaneous fusion would take place and the strangelet would grow as it consumed helium nuclei, giving off large amounts of radiation. At some point it would grow so large that it would fall through the helium containment-wall (consuming every atom it encounters on the way), fall out of the device, and penetrate the concrete floor, tunneling down to the center of the Earth. The result will be the eventual (a period of days or months) conversion of every atom in the Earth to become part of one massive hot strange-matter nucleus. The Moon and a set of artificial satellites will orbit a white-hot strange Earth only about 100 meters in diameter but with approximately the original mass of the Earth (some mass will be lost to radiated heat). Once the strangelet is created, no power on Earth can stop it. Let me repeat: the above disaster scenario is well-described in the BNL Review.

Recognizing that it is insufficient (in the face of the potential devastation that could result) to have as their argument that dangerous strangelet production is unlikely (but possible), the Review authors turn to cosmic ray arguments. The first of two arguments is that the Moon has been bombarded by cosmic rays for millions of years and it still exists as normal matter. The second argument is that cosmic rays collide head on in deep space and have not caused any problems. Both arguments fail so obviously it invites belief that the Review authors are either incompetent or subject to a strong pre-existing bias.

First, let's examine the lunar argument: some cosmic rays have the mass and equivalent energy of a gold atom flying around in the RHIC. However, the Moon is a stationary target, so the center-of-mass (COM) energy is far below that of a collision in the RHIC. Fully acknowledging that this argument fails, the Review authors turn (in apparent desperation) to the head-on cosmic ray collision argument.

Deep space cosmic ray head-on collisions could generate small strangelets. If the strangelets are stable, (long-lived) they could be swept up in the course of years in new star development. If so, they would cause supernovas at a much higher rate than observed; hence stable strangelets are not being created. However, that argument does not speak to the RHIC disaster scenario, which only requires metastable strangelets (not stable ones), so it also fails.

R = P * C

where R is the risk (in dollars), P is the probability that destructive strangelets will be created at BNL, and C is the cost of the destruction of the planet. A lower bound for C can easily be arrived at by assuming that life in the future will be at least as good as it is today if the planet is not destroyed. Then C is the gross international economic product in the last year times the number of years we project the Earth will last without BNL's help in destroying it. That could be about a billion years.

Inspection of the risk formula indicates that we want P to be computed to be quite small, less than 10 to the -18 power (on the order of a nano-nano worry). This formula for risk computation also gives us a reasonable way for deciding how much to spend to convince ourselves that P is small.

How likely is the disaster scenario? Physicists are not able to compute a probability, but they cannot show the probability to be zero. In view of the grave consequences of a mistake here, it makes sense to delay full-power (collision-mode) operation of the RHIC until this likelihood is better understood. Those with career interests at stake here may argue that if we had to be absolutely sure every experiment was safe there would be no scientific progress. The lives of a few hundred or a few thousand people at risk from a science experiment are one thing. The lives of every person and all future lives at risk here are quite another. This safety issue is unprecedented.

Years after startup of the RHIC, there is no evidence that strangelets have been created or that the earth is being consumed. However, that does not mean that the danger has passed. A proper safety review has still not been performed, and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) energies at CERN will be greater and continue to increase.

Richard dot J dot Wagner at gmail dot com

Richard dot J dot Wagner at gmail dot com

Copyright © 2000-2010 by Richard J. Wagner, all rights reserved.

This page established March 8, 2000; last updated by

Rick Wagner,

October 8, 2010.